Nonlinear Objects in Rotor Balancing

Why balancing “does not work”, why influence coefficients change, and how to proceed in real field conditions

Overview

In practice, rotor balancing is almost never reduced to simply calculating and installing a correction weight. Formally, the algorithm is well known and the instrument performs all calculations automatically, but the final result depends far more on the behavior of the object itself than on the balancing device. This is why, in real work, situations constantly arise where balancing “does not work”, influence coefficients change, vibration becomes unstable, and the result is not repeatable from one run to another.

Linear and Nonlinear Vibrations, Their Features, and Balancing Methods

Successful balancing requires understanding how an object reacts to the addition or removal of mass. In this context, the concepts of linear and nonlinear objects play a key role. Understanding whether an object is linear or nonlinear allows the selection of the correct balancing strategy and helps achieve the desired result.

Linear objects hold a special place in this field due to their predictability and stability. They allow for the use of simple and reliable diagnostic and balancing methods, making their study an important step in vibration diagnostics.

Linear vs nonlinear objects

Most of these problems are rooted in a fundamental but often underestimated distinction between linear and nonlinear objects. A linear object, from the balancing point of view, is a system in which, at a constant rotational speed, the vibration amplitude is proportional to the amount of unbalance, and the vibration phase follows the angular position of the unbalanced mass in a strictly predictable way. Under these conditions, the influence coefficient is a constant value. All standard dynamic balancing algorithms, including those implemented in the Balanset-1A, are designed precisely for such objects.

For a linear object, the balancing process is predictable and stable. Installing a trial weight produces a proportional change in vibration amplitude and phase. Repeated starts give the same vibration vector, and the calculated correction weight remains valid. Such objects are well suited both for one-time balancing and for serial balancing using stored influence coefficients.

A nonlinear object behaves in a fundamentally different way. The very basis of the balancing calculation is violated. Vibration amplitude is no longer proportional to unbalance, the phase becomes unstable, and the influence coefficient changes depending on the trial weight mass, operating mode, or even time. In practice, this appears as chaotic behavior of the vibration vector: after installing a trial weight, the vibration change may be too small, excessive, or simply non-repeatable.

What Are Linear Objects?

A linear object is a system where vibration is directly proportional to the magnitude of imbalance.

A linear object, in the context of balancing, is an idealized model characterized by a direct proportional relationship between the magnitude of the imbalance (unbalanced mass) and the vibration amplitude. This means that if the imbalance is doubled, the vibration amplitude will also double, provided the rotor's rotational speed remains constant. Conversely, reducing the imbalance will proportionally decrease the vibrations.

Unlike nonlinear systems, where the behavior of an object may vary depending on many factors, linear objects allow for a high level of precision with minimal effort.

Additionally, they serve as the foundation for training and practice for balancers. Understanding the principles of linear objects helps develop skills that can later be applied to more complex systems.

Graphical Representation of Linearity

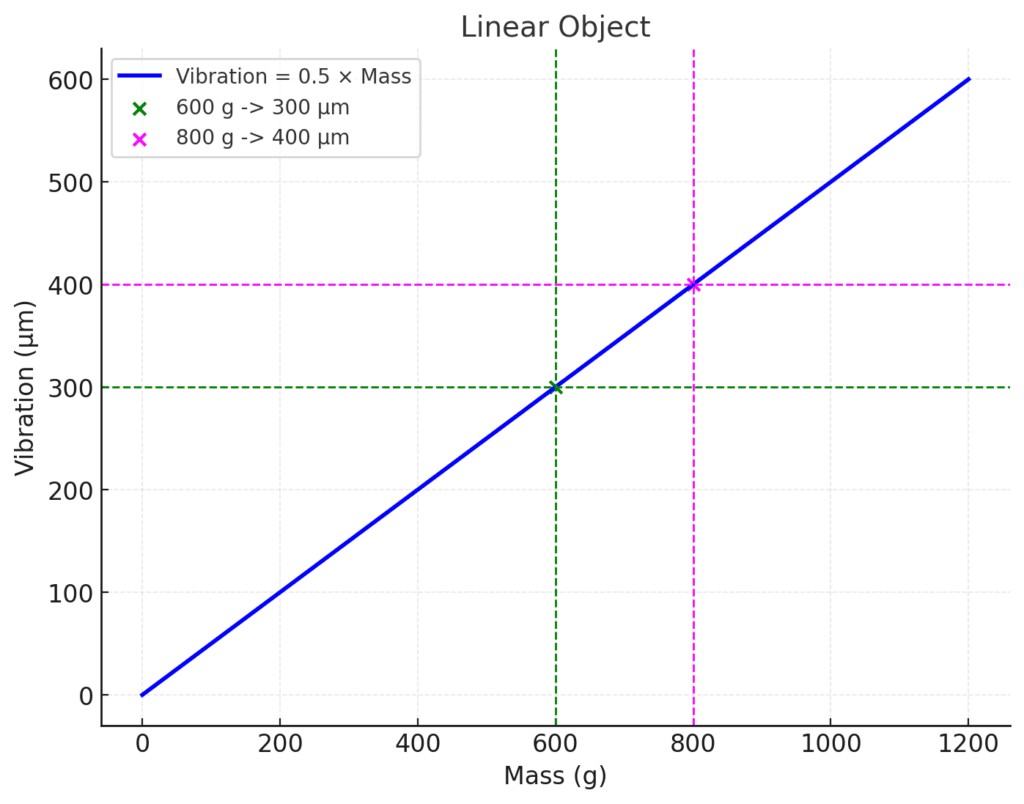

Imagine a graph where the horizontal axis represents the magnitude of the unbalanced mass (imbalance), and the vertical axis represents the vibration amplitude. For a linear object, this graph will be a straight line passing through the origin (the point where both the imbalance magnitude and the vibration amplitude are zero). The slope of this line characterizes the object's sensitivity to imbalance: the steeper the slope, the greater the vibrations for the same imbalance.

Graph 1 illustrates the relationship between the vibration amplitude (µm) of a linear balancing object and the unbalanced mass (g) of the rotor. The proportionality coefficient is 0.5 µm/g. Simply dividing 300 by 600 gives 0.5 µm/g. For an unbalanced mass of 800 g (UM=800 g), the vibration will be 800 g * 0.5 µm/g = 400 µm. Note that this applies at a constant rotor speed. At a different rotational speed, the coefficient will be different.

This proportionality coefficient is called the influence coefficient (sensitivity coefficient) and has a dimension of µm/g or, in cases involving imbalance, µm/(g*mm), where (g*mm) is the unit of imbalance. Knowing the influence coefficient (IC), it is also possible to solve the inverse problem, namely, determining the unbalanced mass (UM) based on the vibration magnitude. To do this, divide the vibration amplitude by the IC.

For example, if the measured vibration is 300 µm and the known coefficient is IC=0.5 µm/g, divide 300 by 0.5 to get 600 g (UM=600 g).

Influence Coefficient (IC): Key Parameter of Linear Objects

A critical characteristic of a linear object is the influence coefficient (IC). It is numerically equal to the tangent of the slope angle of the line on the graph of vibration versus imbalance and indicates how much the vibration amplitude (in microns, µm) changes when a unit of mass (in grams, g) is added in a specific correction plane at a specific rotor speed. In other words, IC is a measure of the object's sensitivity to imbalance. Its unit of measurement is µm/g, or, when imbalance is expressed as the product of mass and radius, µm/(g*mm).

IC is essentially the "passport" characteristic of a linear object, enabling predictions of its behavior when mass is added or removed. Knowing the IC allows solving both the direct problem – determining vibration magnitude for a given imbalance – and the inverse problem – calculating imbalance magnitude from measured vibration.

Direct Problem:

Inverse Problem:

Vibration Phase in Linear Objects

In addition to amplitude, vibration is also characterized by its phase, which indicates the rotor's position at the moment of maximum deviation from its equilibrium position. For a linear object, the vibration phase is also predictable. It is the sum of two angles:

- The angle that determines the position of the rotor's overall unbalanced mass. This angle indicates the direction in which the primary imbalance is concentrated.

- The argument of the influence coefficient. This is a constant angle that characterizes the object's dynamic properties and does not depend on the magnitude or angle of the unbalanced mass installation.

Thus, by knowing the IC argument and measuring the vibration phase, it is possible to determine the angle of the unbalanced mass installation. This allows not only the calculation of the corrective mass magnitude but also its precise placement on the rotor to achieve optimal balance.

Balancing Linear Objects

It is important to note that for a linear object, the influence coefficient (IC) determined in this way does not depend on the magnitude or angle of the trial mass installation, nor on the initial vibration. This is a key characteristic of linearity. If the IC remains unchanged when the trial mass parameters or initial vibration are altered, it can be confidently asserted that the object behaves linearly within the considered range of imbalances.

Steps for Balancing a Linear Object

- Measuring Initial Vibration: The first step is to measure the vibration in its initial state. The amplitude and vibration angle, which indicate the imbalance direction, are determined.

- Installing a Trial Mass: A mass of known weight is installed on the rotor. This helps to understand how the object reacts to additional loads and allows the vibration parameters to be calculated.

- Re-measuring Vibration: After installing the trial mass, new vibration parameters are measured. By comparing them with the initial values, it is possible to determine how the mass affects the system.

- Calculating the Corrective Mass: Based on the measurement data, the mass and installation angle of the corrective weight are determined. This weight is placed on the rotor to eliminate the imbalance.

- Final Verification: After installing the corrective weight, the vibration should be significantly reduced. If the residual vibration still exceeds the acceptable level, the procedure can be repeated.

Note: Linear objects serve as ideal models for studying and practically applying balancing methods. Their properties allow engineers and diagnosticians to focus on developing basic skills and understanding the fundamental principles of working with rotor systems. Although their application in real practice is limited, the study of linear objects remains an important step in advancing vibration diagnostics and balancing.

Placeholder shortcode:

Serial balancing and stored coefficients

Serial balancing deserves special attention. It can significantly increase productivity, but only when applied to linear, vibration-stable objects. In such cases, influence coefficients obtained on the first rotor can be reused for subsequent identical rotors. However, as soon as support stiffness, rotational speed, or bearing condition changes, repeatability is lost and the serial approach stops working.

Nonlinear Objects: When Theory Diverges from Practice

What Is a Nonlinear Object?

A nonlinear object is a system where the vibration amplitude is not proportional to the magnitude of imbalance. Unlike linear objects, where the relationship between vibration and imbalance mass is represented by a straight line, in nonlinear systems this relationship can follow complex trajectories.

In the real world, not all objects behave linearly. Nonlinear objects exhibit a relationship between imbalance and vibration that is not directly proportional. This means the influence coefficient is not constant and may vary depending on several factors, such as:

- Magnitude of Imbalance: Increasing the imbalance can change the stiffness of the rotor's supports, leading to nonlinear changes in vibration.

- Rotational Speed: Different resonance phenomena may be excited at varying rotational speeds, also resulting in nonlinear behavior.

- Presence of Clearances and Gaps: Clearances and gaps in bearings and other connections can cause abrupt changes in vibration under certain conditions.

- Temperature: Temperature changes can affect material properties and, consequently, the vibration characteristics of the object.

- External Loads: External loads acting on the rotor can alter its dynamic characteristics and lead to nonlinear behavior.

Why Are Nonlinear Objects Challenging?

Nonlinearity introduces many variables into the balancing process. Successful work with nonlinear objects requires more measurements and more complex analysis. For instance, standard methods applicable to linear objects do not always yield accurate results for nonlinear systems. This necessitates a deeper understanding of the physics of the process and the use of specialized diagnostic methods.

Signs of Nonlinearity

A nonlinear object can be identified by the following signs:

- Non-proportional vibration changes: As the imbalance increases, vibration may grow faster or slower than expected for a linear object.

- Phase shift in vibration: The vibration phase may change unpredictably with variations in imbalance or rotational speed.

- Presence of harmonics and subharmonics: The vibration spectrum may exhibit higher harmonics (multiples of the rotational frequency) and subharmonics (fractions of the rotational frequency), indicating nonlinear effects.

- Hysteresis: The vibration amplitude may depend not only on the current value of imbalance but also on its history. For example, when imbalance is increased and then decreased back to its initial value, the vibration amplitude may not return to its original level.

Nonlinearity introduces many variables into the balancing process. More measurements and complex analysis are required for successful operation. For example, standard methods applicable to linear objects do not always yield accurate results for nonlinear systems. This necessitates a deeper understanding of the process physics and the use of specialized diagnostic methods.

Graphical Representation of Nonlinearity

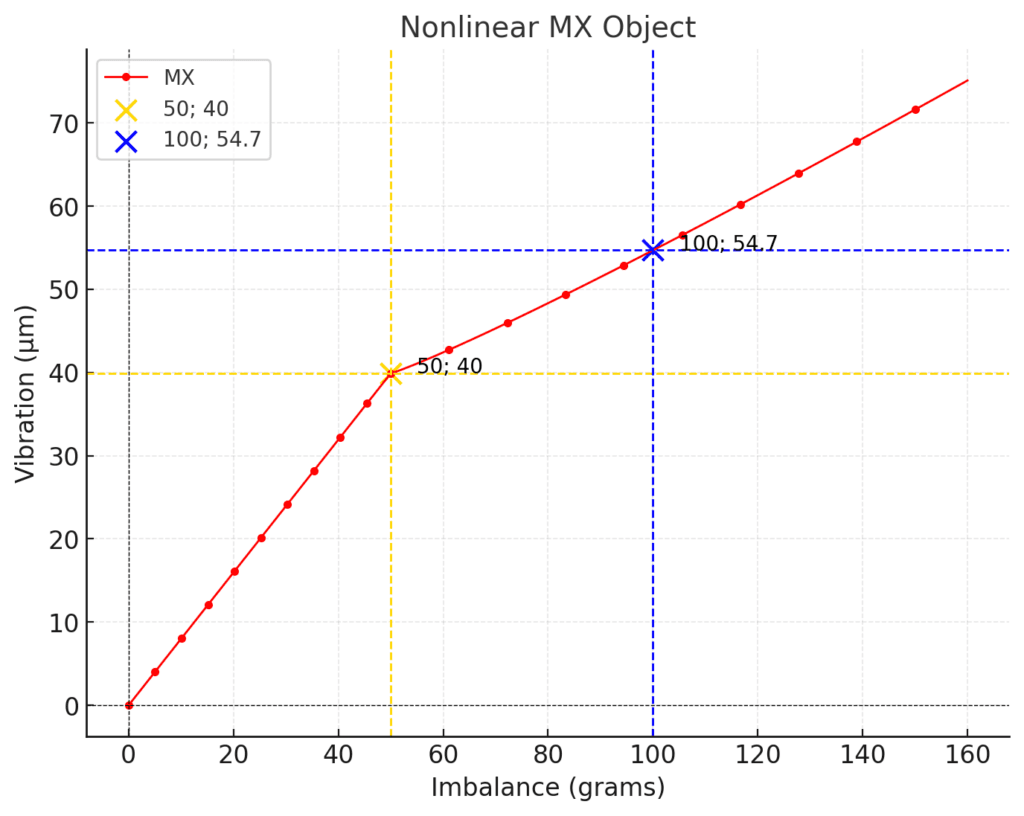

On a graph of vibration versus imbalance, nonlinearity is evident in deviations from a straight line. The graph may feature bends, curvature, hysteresis loops, and other characteristics that indicate a complex relationship between imbalance and vibration.

This object exhibits two segments, two straight lines. For imbalances less than 50 grams, the graph reflects the properties of a linear object, maintaining proportionality between the imbalance in grams and the vibration amplitude in microns. For imbalances greater than 50 grams, the growth of the vibration amplitude slows down.

Examples of Nonlinear Objects

Examples of nonlinear objects in the context of balancing include:

- Rotors with cracks: Cracks in the rotor can lead to nonlinear changes in stiffness and, as a result, a nonlinear relationship between vibration and imbalance.

- Rotors with bearing clearances: Clearances in bearings can cause abrupt changes in vibration under certain conditions.

- Rotors with nonlinear elastic elements: Some elastic elements, such as rubber dampers, may exhibit nonlinear characteristics, affecting the rotor's dynamics.

Types of Nonlinearity

1. Soft-Stiff Nonlinearity

In such systems, two segments are observed: soft and stiff. In the soft segment, the behavior resembles linearity, where the vibration amplitude increases proportionally to the imbalance mass. However, after a certain threshold (breakpoint), the system transitions to a stiff mode, where the amplitude growth slows down.

2. Elastic Nonlinearity

Changes in the stiffness of supports or contacts within the system make the vibration-imbalance relationship complex. For instance, vibration may suddenly increase or decrease when crossing specific load thresholds.

3. Friction-Induced Nonlinearity

In systems with significant friction (e.g., in bearings), the vibration amplitude may be unpredictable. Friction can reduce vibration in one speed range and amplify it in another.

Common causes of nonlinearity

The most common causes of nonlinearity are increased bearing clearances, bearing wear, dry friction, loosened supports, cracks in the structure, and operation near resonance frequencies. Often, the object exhibits so-called soft–hard nonlinearity. At small unbalance levels the system behaves almost linearly, but as vibration increases, stiffer elements of the supports or casing become involved. In such cases, balancing is possible only within a narrow operating range and does not provide stable long-term results.

Vibration instability

Another serious issue is vibration instability. Even a formally linear object may show changes in amplitude and phase over time. This is caused by thermal effects, changes in lubricant viscosity, thermal expansion, and unstable friction in the supports. As a result, measurements taken only minutes apart can produce different vibration vectors. Under these conditions, meaningful comparison of measurements becomes impossible, and the balancing calculation loses reliability.

Balancing near resonance

Balancing near resonance is especially problematic. When the rotational frequency coincides with, or is close to, a natural frequency of the system, even a small unbalance causes a sharp increase in vibration. The vibration phase becomes extremely sensitive to small speed variations. The object effectively enters a nonlinear regime, and balancing in this zone loses physical meaning. In such cases, the operating speed or the mechanical structure must be changed before balancing can be considered.

High vibration after “successful” balancing

In practice, it is common to encounter situations where, after a formally successful balancing procedure, the overall vibration level remains high. This does not indicate an error of the instrument or the operator. Balancing eliminates mass unbalance only. If vibration is caused by foundation defects, loosened fasteners, misalignment, or resonance, correction weights will not solve the problem. In these cases, analyzing the spatial distribution of vibration across the machine and its foundation helps to identify the true cause.

Balancing Nonlinear Objects: A Complex Task with Unconventional Solutions

Balancing nonlinear objects is a challenging task that requires specialized methods and approaches. The standard trial mass method, developed for linear objects, may yield erroneous results or be entirely inapplicable.

Balancing Methods for Nonlinear Objects

- Step-by-step balancing: This method involves gradually reducing imbalance by installing corrective weights at each stage. After each stage, vibration measurements are taken, and a new corrective weight is determined based on the object's current state. This approach accounts for changes in the influence coefficient during the balancing process.

- Balancing at multiple speeds: This method addresses the effects of resonance phenomena at different rotational speeds. Balancing is performed at several speeds near resonance, enabling more uniform vibration reduction across the entire operating speed range.

- Using mathematical models: For complex nonlinear objects, mathematical models describing rotor dynamics while accounting for nonlinear effects can be employed. These models help predict object behavior under various conditions and determine optimal balancing parameters.

The experience and intuition of a specialist play a crucial role in balancing nonlinear objects. An experienced balancer can recognize signs of nonlinearity, select an appropriate method, and adapt it to the specific situation. Analyzing vibration spectra, observing vibration changes as the object's operating parameters vary, and considering the rotor's design features all assist in making the right decisions and achieving the desired results.

How to Balance Nonlinear Objects Using a Tool Designed for Linear Objects

This is a good question. My personal method for balancing such objects starts with repairing the mechanism: replacing bearings, welding cracks, tightening bolts, checking anchors or vibration isolators, and verifying that the rotor does not rub against stationary structural elements.

Next, I identify resonance frequencies, as it is impossible to balance a rotor at speeds close to resonance. To do this, I use the impact method for resonance determination or a rotor coast-down graph.

Then, I determine the sensor's position on the mechanism: vertical, horizontal, or at an angle.

After trial runs, the device indicates the angle and weight of the corrective loads. I halve the corrective load weight but use the angles suggested by the device for rotor placement. If the residual vibration after correction still exceeds the acceptable level, I perform another rotor run. Naturally, this takes more time, but the results are sometimes inspiring.

The Art and Science of Balancing Rotating Equipment

Balancing rotating equipment is a complex process that combines elements of science and art. For linear objects, balancing involves relatively simple calculations and standard methods. However, working with nonlinear objects requires a deep understanding of rotor dynamics, the ability to analyze vibration signals, and the skill to choose the most effective balancing strategies.

Experience, intuition, and continuous skill improvement are what make a balancer a true master of their craft. After all, the quality of balancing not only determines the efficiency and reliability of equipment operation but also ensures the safety of people.

Measurement repeatability

Measurement issues also play a major role. Incorrect installation of vibration sensors, changes in measurement points, or improper sensor orientation directly affect both amplitude and phase. For balancing, it is not enough to measure vibration; repeatability and stability of measurements are critical. This is why, in practical work, sensor mounting locations and orientations must be strictly controlled.

Practical approach for nonlinear objects

Balancing a nonlinear object always begins not with installing a trial weight, but with evaluating vibration behavior. If amplitude and phase clearly drift over time, change from one start to another, or react sharply to small speed variations, the first task is to achieve the most stable operating mode possible. Without this, any calculations will be random.

The first practical step is choosing the correct speed. Nonlinear objects are extremely sensitive to resonance, so balancing must be performed at a speed as far as possible from natural frequencies. This often means moving below or above the usual operating range. Even if vibration at this speed is higher, but stable, it is preferable to balancing in a resonant zone.

Next, it is important to minimize all sources of additional nonlinearity. Before balancing, all fasteners should be checked and tightened, clearances eliminated as much as possible, and supports and bearing units inspected for looseness. Balancing does not compensate for clearances or friction, but it may be possible if these factors are brought to a stable condition.

When working with a nonlinear object, small trial weights should not be used out of habit. Too small a trial weight often fails to move the system into a repeatable region, and the vibration change becomes comparable to instability noise. The trial weight must be large enough to cause a clear and reproducible change in the vibration vector, but not so large that it drives the object into a different operating regime.

Measurements should be performed quickly and under identical conditions. The less time passes between measurements, the higher the chance that the dynamic parameters of the system remain unchanged. It is advisable to perform several control runs without changing the configuration to confirm that the object behaves consistently.

It is very important to fix vibration sensor mounting points and their orientation. For nonlinear objects, even a small sensor displacement can cause noticeable changes in phase and amplitude, which may be mistakenly interpreted as the effect of the trial weight.

In calculations, attention should be paid not to exact numerical agreement, but to trends. If vibration consistently decreases with successive corrections, this indicates that balancing is moving in the right direction, even if influence coefficients do not formally converge.

It is not recommended to store and reuse influence coefficients for nonlinear objects. Even if one balancing cycle is successful, during the next start the object may enter a different regime and the previous coefficients will no longer be valid.

It should be remembered that balancing a nonlinear object is often a compromise. The goal is not to achieve the lowest possible vibration, but to bring the machine into a stable and repeatable condition with an acceptable vibration level. In many cases, this is a temporary solution until bearings are repaired, supports are restored, or the structure is modified.

The main practical principle is to stabilize the object first, then balance it, and only after that evaluate the result. If stabilization cannot be achieved, balancing should be considered an auxiliary measure rather than a final solution.

Reduced correction weight technique

In practice, when balancing nonlinear objects, another important technique often proves effective. If the instrument calculates a correction weight using a standard algorithm, installing the full calculated weight frequently makes the situation worse: vibration may increase, the phase may jump, and the object may shift into a different operating mode.

In such cases, installing a reduced correction weight works well — two or sometimes even three times smaller than the value calculated by the instrument. This helps avoid “throwing” the system out of the conditionally linear region into another nonlinear regime. In effect, the correction is applied gently, with a small step, without causing a sharp change in the dynamic parameters of the object.

After installing the reduced weight, a control run must be performed and the vibration trend evaluated. If the amplitude steadily decreases and the phase remains relatively stable, the correction can be repeated using the same approach, gradually approaching the minimum achievable vibration level. This step-by-step method is often more reliable than installing the full calculated correction weight at once.

This technique is especially effective for objects with clearances, dry friction, and soft–hard supports, where full calculated correction immediately drives the system out of the conditionally linear zone. Using reduced correction masses allows the object to remain in the most stable operating regime and makes it possible to achieve a practical result even where balancing is formally considered impossible.

It is important to understand that this is not an “instrument error”, but a consequence of the physics of nonlinear systems. The instrument correctly calculates for a linear model, while the engineer adapts the result in practice to the real behavior of the mechanical system.

Final principle

Ultimately, successful balancing is not merely about calculating a weight and an angle. It requires understanding the dynamic behavior of the object, its linearity, vibration stability, and distance from resonance conditions. The Balanset-1A provides all necessary tools for measurement, analysis, and calculation, but the final result is always determined by the mechanical condition of the system itself. This is what distinguishes a formal approach from real engineering practice in vibration diagnostics and rotor balancing.

Questions & answers

This is a sign of a nonlinear object. In a linear object, vibration amplitude is proportional to the amount of unbalance, and the phase changes by the same angle as the angular position of the weight. When these conditions are violated, the influence coefficient is no longer constant and the standard balancing algorithm starts to produce errors. Typical causes are bearing clearances, loosened supports, friction, and operation near resonance.

A linear object is a rotor system in which, at the same rotational speed, vibration amplitude is directly proportional to the magnitude of unbalance, and the vibration phase strictly follows the angular position of the unbalanced mass. For such objects, the influence coefficient is constant and does not depend on the mass of the trial weight.

A nonlinear object is a system in which the proportionality between vibration and unbalance and/or the constancy of the phase relationship is violated. Vibration amplitude and phase begin to depend on the mass of the trial weight. Most often this is associated with bearing clearances, wear, dry friction, soft–hard supports, or the engagement of stiffer structural elements.

Yes, but the result is unstable and depends on the operating mode. Balancing is possible only within a limited range where the object behaves conditionally linearly. Outside this range, influence coefficients change and result repeatability is lost.

The influence coefficient is a measure of vibration sensitivity to changes in unbalance. It shows how much the vibration vector will change when a known trial weight is installed in a given plane at a given speed.

The influence coefficient is unstable if the object is nonlinear, if vibration is unstable over time, or if resonance, thermal warm-up, loosened fasteners, or changing friction conditions are present. In such cases, repeated starts produce different amplitude and phase values.

Stored influence coefficients may be used only for identical rotors operating at the same speed, under the same installation conditions and support stiffness. The object must be linear and vibration-stable. Even a slight change in conditions makes the old coefficients unreliable.

During warm-up, bearing clearances, support stiffness, lubricant viscosity, and friction level change. This alters the dynamic parameters of the system and, as a result, changes vibration amplitude and phase.

Vibration instability is a change in amplitude and/or phase over time at a constant rotational speed. Balancing relies on comparing vibration vectors, so when vibration is unstable, the comparison loses meaning and the calculation becomes unreliable.

There are inherent structural instability, slow “creeping” instability, variation from start to start, warm-up-related instability, and resonance-related instability when operating near natural frequencies.

In the resonance zone, even a small unbalance causes a sharp increase in vibration, and the phase becomes extremely sensitive to small changes. Under these conditions, the object becomes nonlinear and the balancing results lose physical meaning.

Typical signs are a sharp increase in vibration with small speed changes, unstable phase, broad humps in the spectrum, and high sensitivity of vibration to minor RPM variations. A vibration maximum is often observed during run-up or coast-down.

High vibration can be caused by resonance, loosened structures, foundation defects, or bearing problems. In such cases, balancing will not eliminate the cause of vibration.

Vibration displacement characterizes the motion amplitude, vibration velocity characterizes the speed of this motion, and vibration acceleration characterizes the acceleration. These quantities are related, but each is better suited to detecting certain types of defects and frequency ranges.

Vibration velocity reflects the energy level of vibration over a wide frequency range and is convenient for assessing the overall condition of machines according to ISO standards.

Correct conversion is possible only for single-frequency harmonic vibration. For complex vibration spectra, such conversions provide only approximate results.

Possible reasons include resonance, foundation defects, loosened fasteners, bearing wear, misalignment, or object nonlinearity. Balancing removes unbalance only, not other defects.

If mechanical defects are not detected and vibration does not decrease after balancing, it is necessary to analyze the vibration distribution over the machine and the foundation. Typical signs are high vibration of the casing and base, and phase shifts between measurement points.

Incorrect sensor installation distorts amplitude and phase, reduces measurement repeatability, and can lead to incorrect diagnostic conclusions and erroneous balancing results.

Vibration is distributed unevenly throughout the structure. Stiffness, masses, and mode shapes differ, so amplitude and phase can vary significantly from point to point.

As a rule, no. Wear and increased clearances make the object nonlinear. Balancing becomes unstable and does not provide a long-term result. Exceptions are possible only with design clearances and stable conditions.

Starting creates high dynamic loads. If the structure is loosened, the relative positions of elements change after each start, leading to changes in vibration parameters.

Serial balancing is possible for identical rotors installed under identical conditions, with vibration stability and absence of resonance. In this case, influence coefficients from the first rotor can be applied to subsequent ones.

This is usually due to changes in support stiffness, assembly differences, changes in rotational speed, or transition of the object into a nonlinear operating regime.

Reduction of vibration to a stable level while maintaining repeatability of amplitude and phase from start to start, and the absence of signs of resonance or nonlinearity.

0 Comments